Professionalism and Pay in Women's Football

Talkin' about real money: Payrolls, CBAs and salary caps around the world

For those of you who dropped by after my Women’s Football Finance post, thanks! Here’s another women’s-soccer related post for you, covering “the other half of the story” - what the players are making, or should make, or will make as things develop, along with the story of the game professionalizing around the world and what that looks like. Who’s making big money, who’s getting by, and how is that changing? Where and on what terms do players have job security? What does it mean to be a “professional league”, really? Or to have a “professional environment” at your club?

If you haven’t read it, here’s my previous post on the game’s underlying economics: club revenues, league audience growth (in broadcasting and attendance), team ownership becoming a hot commodity, trends and the big-time leagues. I won’t recap it, but if you haven’t read it, it might offer some helpful background (including why I care about this topic and think it’s important).

I plan to write a third installment, on the economics of the national-team game. Eventually. Among other plans.1

TLDR: Women Ballers have now “Made It”

Look, I’m long-winded; being so costs me less than hiring an editor would. But as a preview, here’s the main points that we’ll get into:

The top of the pyramid is getting meaningfully higher, with 7-figure deals now being thrown around by the US and Europe’s top clubs to recruit elite talent.

The base of that pyramid is also being broadened: Rapidly-rising minimum salaries ($20-30k in a few places), likewise for average salaries ($40-50k in some European leagues, and upwards of $125k in the NWSL). With new teams forming (and leagues professionalizing globally), the # of pro jobs available is expanding.

The proliferation of CBAs around the various pro women’s leagues is driving those changes and salary floors. Each offers meaningful minimum salaries and roster sizes, mandates (most of) the trappings of professional sports teams, and means that the days of players having a bartending gig on the side are mostly over - at least in those leagues, for those good enough to make it there.

Pro players are still subject to the iron law of compensation for performers: you eat what you kill. We should expect pay and payrolls to continue to rise, but be disproportionately slanted toward the most marketable stars, and dependent on the continued growth of the audience / market for the sport.

Beyond the professional ranks are thousands of first-division players in other countries, a majority of whom have to blend a football career with an outside job or studies. Taking the leap to professionalization eliminates these stresses and conflicts, yielding a better on-field product that is more attractive to fans, and can “generate its own oxygen” economically. But the clubs or FAs have to lead.

In short, revenue growth will mostly benefit the top players, absent non-economic forces intruding. It is those CBAs that are creating livable pay and conditions for the average pro women’s footballer, by forcing clubs to share the gains more broadly.

Paid? I’d play this game for free!

Women’s soccer was banned in many of the world’s biggest soccer countries, from roughly the 1920s to the 1970s. It was forbidden for women to play football, even for charity matches. At the time the bans began, matches were selling tens of thousands of tickets, so there was no doubt about the fan interest and market potential. In 1967, a carpenter in Kent in the southeast of England, Arthur Hobbs, thought this was all nonsense, and staged a women’s tournament which became the precursor to the FA Women’s Cup. National associations for women’s football formed (in defiance of the men’s FAs), a non-FIFA Women’s World Cup was organized in Mexico in 1971,2 and gradually the first wave of the feminist movement re-opened the sport to women.

Although there had been female professionals before and immediately after the ban era, the hiatus prevented (or at least stalled) the development of player training clubs and large club fanbases in parallel to that of boys/men, and so pro women players were few and far between. Those who did play were more like mercenary guns-for-hire than pursuing any sort of stable and prosperous career. But with the passage of Title IX in the US in 1972, substantial resources began to enter women’s soccer through the college system, bootstrapping a presence for the US for the game, despite lacking the baseline of the sport’s cultural importance as in other countries.3 Even the USWNT, which became a source of American national pride, was distinctly unprofessional for a decade or so,4 right up until their 1999 Women’s World Cup run to glory gave them the cultural cachet (and budget) to change the game.

With Sweden’s Damallsvenskan becoming the first women’s pro league in 1988, that began to change. As my last post detailed, 25 years and lots of failed ventures later, women’s soccer finally was able to start supporting full rosters of women who were all paid to play. But even as the NWSL launched in 2013, there were still only 2 other leagues in the world where most women were paid - Sweden and Germany - and even there, some clubs had partially-amateur rosters and minimal payrolls. Frankly, the NWSL’s initial minimum salary of $6,000 only amounted to semi-pro status for the numerous players who received it. So the advent of a league where (1) all the players make enough to live on, and can thus devote themselves fully to soccer without having to take side jobs, and also (2) the teams bring in enough money to pay players a living wage and still grow and survive, is actually a very recent thing, as we’ll explore.

But recent though it may be, that world is now upon us, and there is no better evidence of it than the 2022 collective-bargaining agreement (CBA) between the NWSL and its Players Association. So let’s look at women’s football again, but this time from the perspective of the players.

Status Symbol: Professionalism and FIFA

Starting in 2021, FIFA hired Deloitte to produce a “Women’s Benchmarking Report” annually, now in its 3rd edition5. They surveyed clubs and leagues around the world, and did an admirable job of going beyond the most-obvious and most-developed markets for women’s football. The report examines the state of the game - be it pro or otherwise - in initially 25, then 30, now 34 countries’ leagues, with responses from over 300 clubs as well as the leagues themselves. The intended audience seems to be executives at national Football Associations around the world as they consider what’s best for the women’s game, but there are a lot of nuggets in there to enlighten an informed, curious fan.

The first is the steady forward march of professionalism. To understand the report’s data on that front, we first need clarity on our terms.

What’s a “Professional”?

For most of us, the term “professional athlete” implies someone who can fully devote themselves to training and playing their sport, so that they give the best performance that they could possibly muster. But in FIFA’s definition, in the report and elsewhere, “professionals” are those who “Have a written employment contract with a club, and are paid more for their footballing activities than the expenses they effectively incur”. Read that again: it only entails (A) a contract, and (B) having, at minimum, their expenses paid. Now to me, that sounds like the definition of “semi-pro”, i.e. those who make some money from playing, they’re not paying to play, but can’t necessarily make it their primary source of income and devote all their time to it.6 Certainly this shift matters - the employment contract gives them various legal rights, plus pride and dignity - but if you can pay players their expenses plus a mere pittance, that’s not a career for them. Luckily, the report also asks the leagues for the % of players for whom “football was the primary source of [their] income” - to me, that’s the real definition of “professional”7. So although the report focuses on the % of players who are “professional” under FIFA’s definition, I will use “semi-pro” and “pro” for the two respective descriptions, or “Contracted” and “FPIS” (Football as Primary Income Source) to avoid confusion.8 Because the difference really matters in assessing the progress toward making women’s football a peer to other pro sports.

Confusingly, leagues are also variously referred-to as semi-professional or fully-professional, under a blend of the above definitions. The terms are sort of thrown around flexibly in discussions of women’s football, for the convenience of the author’s agenda. The definitions I find to be useful are that a league is semi-professional when a clear majority of players are at least semi-pro (Contracted), and a nontrivial minority make their primary living from the sport (FPIS). And a league is fully-professional when substantially all players are signed to decently-salaried contracts, even if the minimum salaries are not anything impressive. In my view, merely allowing professional contracts does not make your league “professional” - players lacking them must be a rare exception. That doesn’t require 100%, though, as there will always be fringe roster players on short-term deals or trials who get counted as semi-pro or amateur.

For our purposes here:

I’ll consider a league semi-professional if at least 80% of its players have contracts (“professional” players per FIFA, “semi-pro” or “contracted” per me).

I’ll consider a league fully-professional if at least 80% of its players report having football as their primary source of income (i.e. are “full-time professionals”).

For ratios between 60-80%, it’s a gray area, we’ll use some judgment and other signals to sort it out. But below 60%, I think a league clearly lacks the status.

So for example, Argentina’s league “went professional” in 2019, but as of the latest report in 2023, only 60% of players were Contracted and only 57% made their primary income through football (FPIS). So if they’re fielding ~40% amateurs, I’d call them barely semi-pro. Whereas, Spain’s Liga F change to professional status in 2022 came alongside a CBA with their players (which we’ll discuss shortly) that set a meaningful salary floor9 for all players on all teams, and they report 99% Contracted and 95% FPIS, so they meet anyone’s definition of a fully-professional league. Players might not be happy with those salary floors, but they are not token amounts, either.

Enough with the Lawyering, Get to the Data

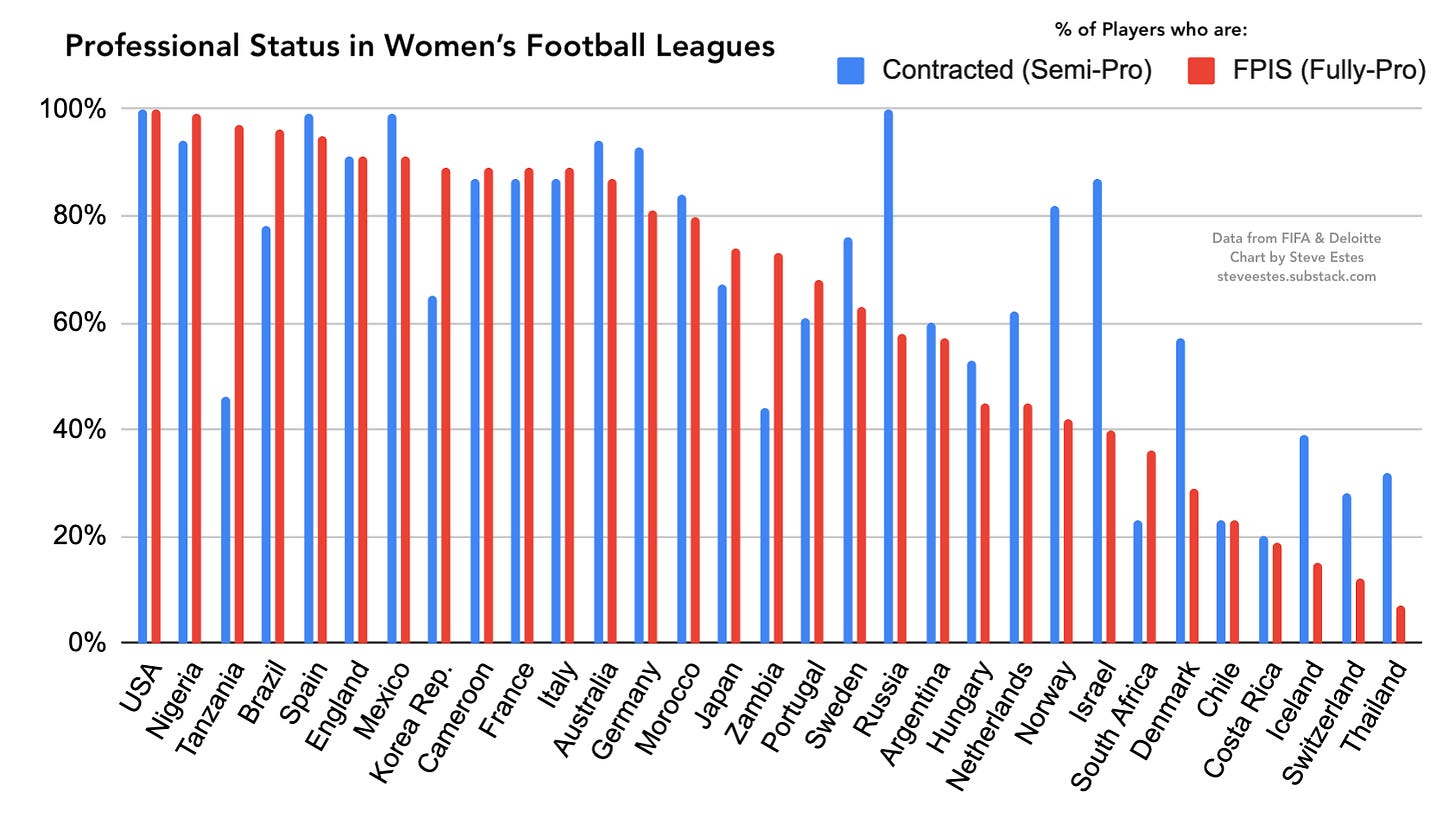

Fine, fine, here’s the Contracted and FPIS status for the 31 leagues who gave it in 2023:

Observations:

It’s sorted by FPIS %, and the group above our 80% threshold for “fully-professional” includes 7 of the Big 8 leagues we discussed last time (USA, ENG, MEX, FRA,10 AUS, GER, JPN, but not SWE). Sweden’s numbers are notably low given their lengthy history as a cradle of women’s pro football.

Above the “pro” cutoff are some newer entrants, too: Spain, Italy, Brazil, Nigeria, South Korea, Morocco and Cameroon. The first two are widely reported-on, but the latter 5 I would call “pleasant surprises”.

It also shows that some countries’ leagues may have been unclear on the question, based on the blue bar (Contracted %) being well below the red bar (Football as Primary Income Source %), particularly S. Korea, Tanzania, Zambia and South Africa. Taken literally, that would imply that some players lack a contract, but nevertheless make their primary living from football. Perhaps they went with an interpretation of expressing FPIS as a fraction of Contracted players only, and Contracted as a % of all players. Or a similar misunderstanding. See footnote #6.

On the far right we have clearly-amateur leagues, including Thailand, Switzerland, Iceland, Costa Rica, etc. And then in the middle is our gray area, the 9 leagues between (eyeballin’ it) pro Japan and amateur South Africa. We’ll need other context to assess their development status.

I would caution against an interpretation that regards a league farther to the left as “more professional”. Above that 80% threshold, differences between leagues may turn on the whims of whoever in a given league office gathered the data together that day, in between handling a dozen other matters. How are contracts registered? How rigidly are rosters and practice squads tracked? How deeply did they care about data accuracy, vs just clicking submit and getting Deloitte off their back? We don’t know. Basically, these numbers should be read with error bars: large differences are meaningful, small differences are probably noise.

Also, England for whatever reason didn’t answer most questions for 2023, including these, so we’ve got their 2021 number up there for completeness’ sake.

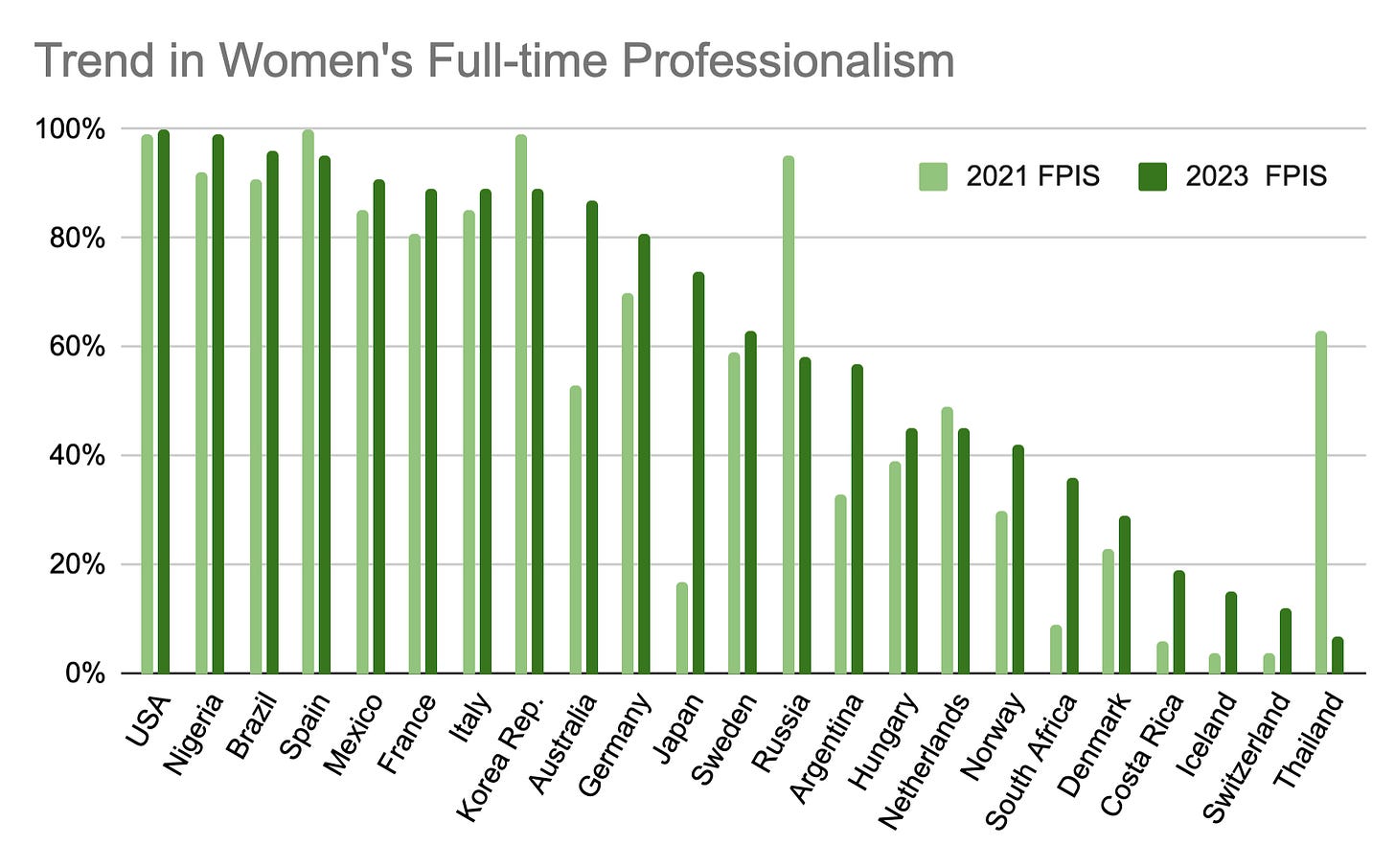

This is the third year they’ve done the survey, so we can compare year-over-year growth trends, too:11

Just about every country providing data had their FPIS number tick up over the past two years. Several had dramatic, 20%+ jumps upwards: Japan (17% → 74%, as their new fully-pro league launched), Australia (53% → 87%), Argentina (33% → 57%), and South Africa (9% → 36%). Two had substantial drops: Thailand went from 63% down to 7% (I’ll chalk that up to a submission / translation error), and Russia down from 95% to 58%, possibly a matter of definitions, or more likely a “didn’t care the first time around” situation.12 FWIW, I buy Russia’s 2023 number (58%), given context clues.

The % Contracted trend doesn’t really tell us anything, other than “people really didn’t put a lot of care into their 2021 submissions”. The large jumps up for Argentina and Italy speak to their leagues professionalizing, similar to their jumps in FPIS. The jumps downward, where the blue lines stick up well past the red, I attribute to submission carelessness in the 2021 figures - I don’t think it reflects a mass abandonment of player contracts in those leagues, which is what it would mean if taken literally.

League Context for Professionalism

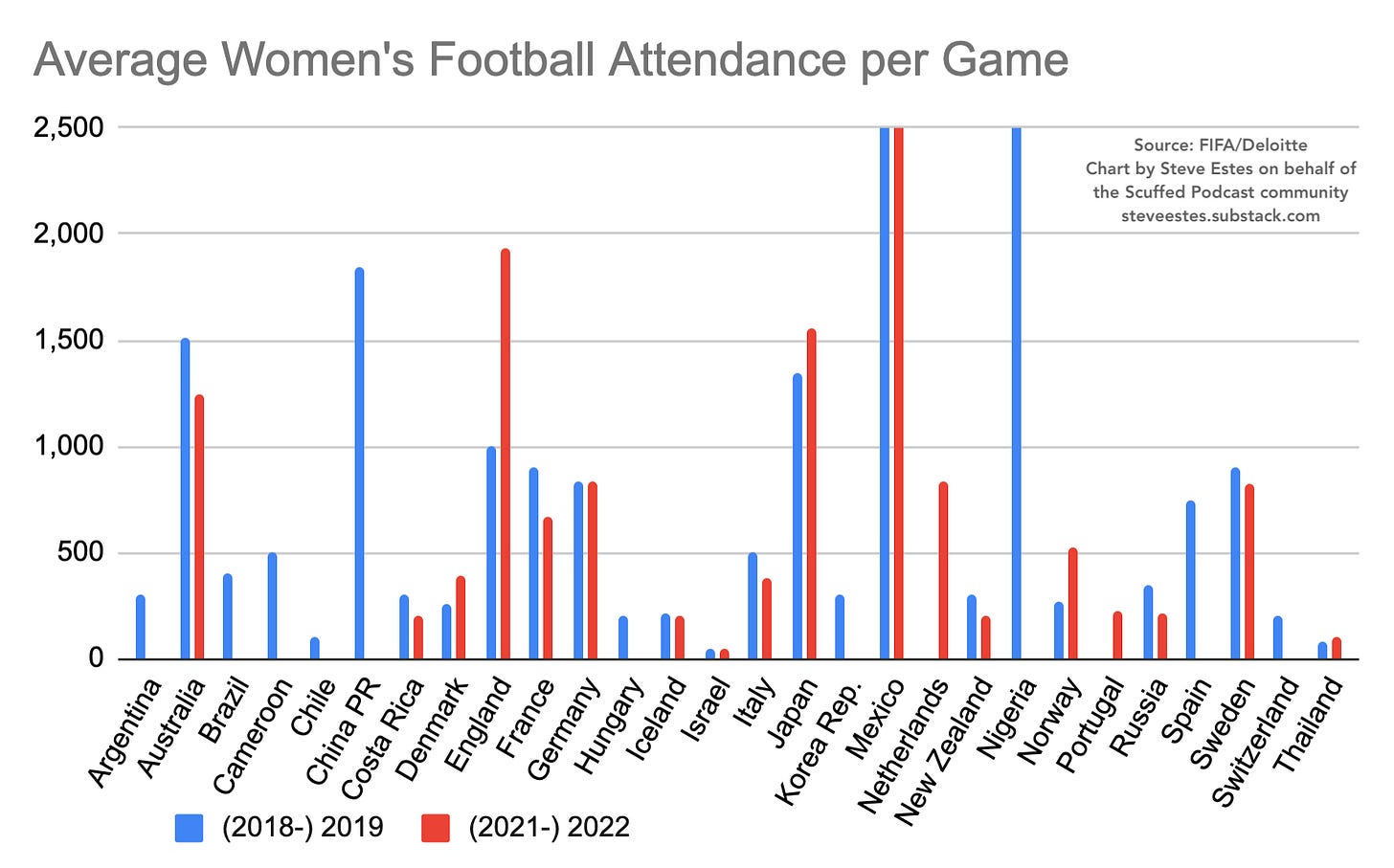

How much stock should we put in these assertions by the leagues? One clue is to compare their average attendance per game. In the 2021 report, the leagues were asked for their 2019 average attendance (or 2018-19), i.e. the last pre-pandemic season. We can show that plus the 2023 report, which gave 2021-22 or 2022 attendance:13

Notes:

9 leagues gave numbers for 2019, but not for 2022. 2 gave numbers for 2022, but not for 2019. Only 16 gave numbers both years. It is what it is.

We can see the financial strength and support of the Big 8 Leagues, with numbers popping out for Australia, England, Japan and Mexico, with France, Germany and Sweden not far behind (and NWSL too high to even put on here).

Mexico’s numbers were 3,000 and 3,100 respectively (but we knew they were big), cropped for the sake of making the others readable. Unexpected is the report from Nigeria of 3,000 / game in 2019 (!), and 1,840 in China. It’s for this reason I suspect Nigeria’s other stats above are “legit”, along with Spain. Also, the crowd sizes in the Netherlands are outpacing their professionalism.

Whereas, the popularity of Italy, Brazil, Cameroon and Korea, as suggested by the Pro/Semipro numbers, are not seen here in the form of butts-in-seats. Likewise Russia and Portugal, drawing 200-300 per game: it’s hard to believe that those numbers could support paying fully-professional rosters, or get sponsors excited.

These numbers are now 4+ years old, and a lot has changed. For example, we know from our last post that Germany and England’s attendance has more than doubled, while Australia and Japan have tailed off a little. But aside from our Big 8, we don’t have more recent annual numbers than this.

Another view into the question of “are they really professional?” can be found in Average Ticket Prices (from 2022 report) and Average Revenue Per Club (from 2021). We’ll contextualize those figures against each country’s median wage:14

Japan, England and USA are charging as if demand exceeds supply. Norway and Sweden are above the curve too. Meanwhile, they’re all but giving tickets away in Italy, Netherlands, China and Denmark. But then again, we know matchday revenue is only a small slice of each club’s financial resources, which were:15

Japan breaks the chart here with $1.65M average revenue per club. China is surprisingly high ($1.1M) for how little they’re seen on the global stage, in terms of players playing abroad, or national-team success in the last 20 years; apparently they are throwing money at the problem for that very reason. Some of the other standouts among rich countries are the usual suspects (England, Spain, France), joined by Norway. Among poorer countries, Nigeria, Mexico and Brazil are ahead of their curve, with South Africa right there with them. And the USA, among others, declined to provide a number.

If the median-wage context is too tough to mentally adjust for, here’s a more normalized view: average numbers of non-playing staff per club. This shows full-time Technical (i.e., coaching & training) staff, and Admin (i.e. business) staff, from the 2021 report. Since having staff is more optional than having players, this speaks to the “professional atmosphere” in each league, how much support the players are getting at their club. Although obviously that will vary considerably among clubs in a country.

The USA’s number there for Admin Staff per club is actually 25.4, I just edited it down because it would break the axis otherwise. You can see that the Nordic countries are getting by on shoestring organizations, despite their relative wealth. And that certain countries are investing very heavily in building professional organizations, even if it means funding losses until the revenue catches up - that seems to include Italy, China, Brazil, Colombia, Russia, and even Argentina. And tops of all leagues other than the USA, in terms of support staff, is Nigeria, at over 18 per club.

While we’re talking about staff, we might as well note the number of (full-time) league staff, as well.

Those commissioners are sure doing a lot of grunt work in some of the lesser leagues. Meanwhile, we again see Nigeria (15 league staff, #5 by this measure) reinforcing that it’s a legitimate, financially stable and well-supported league, in spite of any assumptions we might make to the contrary due to gender equity and human development in that country.

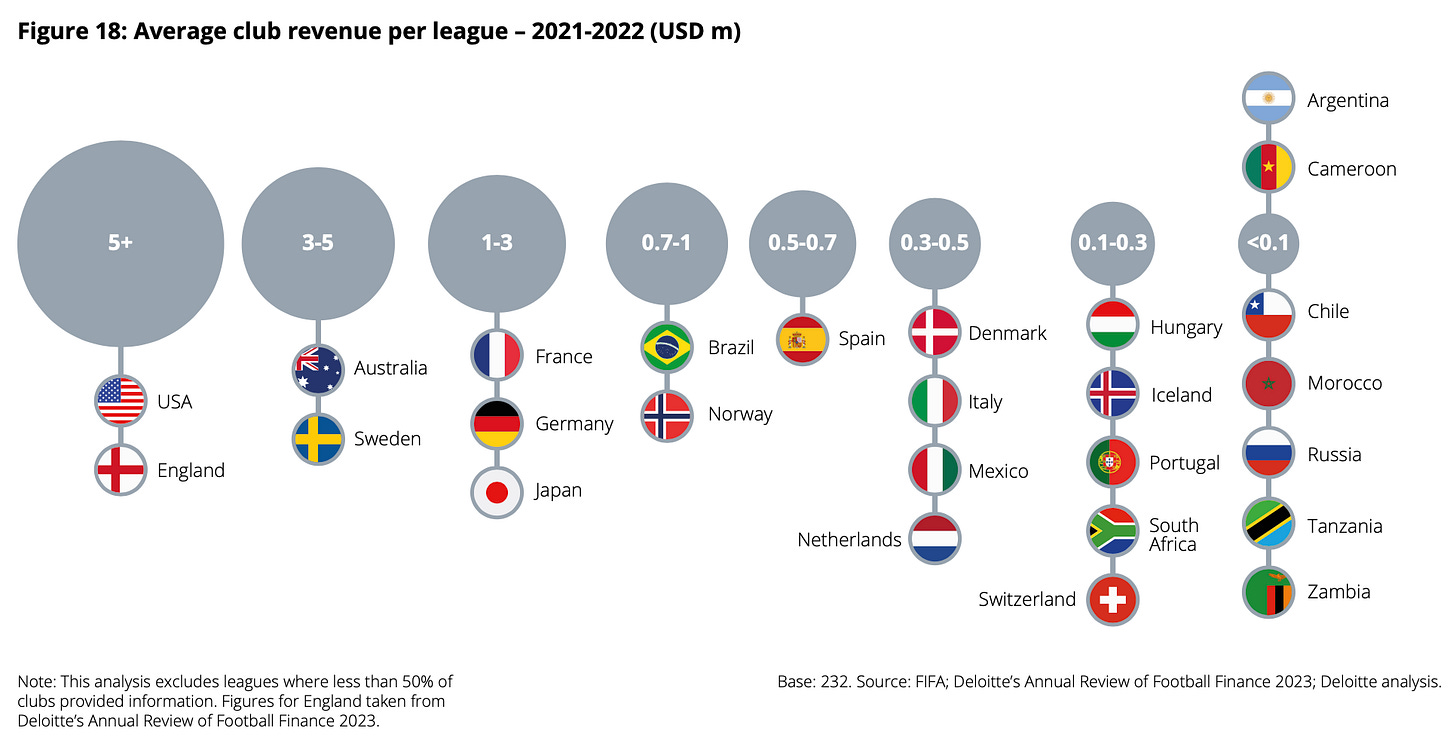

The 2023 report also added this country grouping for average revenue per club, albeit without reporting specific numbers for each country:

Those first 3 revenue groups include 7 of our Big 8 (Mexico a bit lower), with Brazil and Spain coming on strong (and Norway just coasting, not really growing). It confirms Sweden’s status as a league with top resources, even if their FPIS and Contract percentages are surprisingly low. It likewise puts doubts on the status of Morocco, Tanzania and Cameroon, despite their strong showings by those measures.

My conclusion of the above is that there are, broadly, a few tiers of leagues when it comes to professionalism and the resources you’d expect to go along with that status:

Tier 1, The Big Girls: USA (NWSL) and ENG (WSL), plus a few continental peer clubs, have full-time pro rosters, paid B-teams, quality training grounds, large support staffs, etc. Nobody could tour one of these clubs16 and not be impressed by the professional standards on display, from facilities to coaching. They are categorically different even from the other definitely-pro leagues.

Tier 2, Fully Pro: The rest of the Big 8 - AUS, SWE, GER, JPN, FRA, MEX - and now joined by Spain and Nigeria. All can afford decent salaries, the clubs make enough revenue on their own to not be constantly worried, fans are numerous and engaged, most players on most teams can be full-time and not take a second job.

Tier 3, Challengers: China, Brazil, Italy, Cameroon, Morocco and South Korea. There’s good evidence that these leagues are fully professional, but some yellow flags from other directions make me think there’s reason to doubt that the average player in these leagues is actually a full pro. With better data, they could jump up. Top clubs in these leagues (e.g. AS FAR in Morocco) can wrangle with bigger fish.

Tier 4, Semi Pro: Argentina, Colombia, Russia, Tanzania, Portugal, Netherlands, Norway, Zambia. There may be some fully-pro players or clubs in these leagues, but the frequency is probably low, and most players aren’t paid enough to focus just on their sport. The average player has a contract and is paid expenses, maybe a small stipend, but not enough to live on or avoid having a day job. Tanzania (and arguably Zambia) are reporting numbers maybe in line with a higher tier, but the peripheral data is too thin to draw a firm conclusion on it today.

Tier 5, Amateur: These leagues may have some pro players, or teams that are more- or fully-pro, but the average player is unpaid. The players mostly all have day jobs. Hungary, Denmark, Iceland, South Africa, Thailand, Costa Rica, Chile, Switzerland, Israel.

This tiering allows us to revisit some of the data above and apply our groupings to it:

Although this data is from a survey in 2021, before Spain and Italy went pro, clearly they belonged closer to the Fully-Pro group even at the time. Brazil and Colombia are candidates to join them, by this measure. China and Russia offer less data transparency, but if we take their numbers at face value, their clubs are investing in pro-level amounts of support staff. And while Germany and Australia have gotten their financial act together since this report, and one might fairly ask what France and Sweden are doing (the latter’s strategic decisions are often suspect). Sweden, at least, reported having much higher amounts of staff redundancies than average as a result of COVID-19, with ~70% of clubs making pandemic layoffs. We can hope they and the others have staffed up in the last ~3 years.

Lastly, FIFA’s report also does not include some countries’ leagues which have reason to suggest might be significant, or decently far along the development curve. Of these, Peru, Vietnam, Ghana, Austria and Czechia are notable in their absence. Ghana is one of the top 10 countries for international transfers; Czechia is ranked #6 in the UEFA Women’s Association Rankings; Peru’s league has 14 teams playing in 10k+ seat stadiums and has been around for almost 30 years. So there’s more to this story than what the report is able to tell. But despite imperfections, the Deloitte report is already a great resource to learn from.

How to Think About This Evolution

To put the forward progress of professionalism in context, it’s worth reminding ourselves of the history of the professionalizing of the men’s game. After decades of wrangling over amateur status, the first season of the first league allowing paid professionals (the English Football League) was played in 1888-1889. It was then 35 years until the first fully professional league (i.e. everyone is paid) was established - Austria’s, in 1924. Most of what are today the world’s top leagues began professional play in the 1920s and 1930s. The whole system of promotion and relegation, where teams who win lower divisions move up, and teams at the bottom of upper divisions move down, was a solution to the problem that the proliferation of professional clubs, and fanbases, had outpaced the readiness of national governance and league organizing. They had more teams than could reasonably compete in a league together, and pro/rel offered a solution that was at least somewhat fair to all involved.

The example of (West) Germany is instructive. An explosion of clubs (with many players paid under the table) saw a prewar situation of 16 (!) regional top divisions. Compare that to the US’s situation of high-level amateur / semi-pro women’s leagues today, which between the WPSL / W-League / UWS total over 200 clubs. Only in 1945 did Germany’s DFB start allowing semi-professional status: a small monthly salary maximum of DM 120 (about $5000 / month today), with additional amounts paid under the table. When they finally organized a national league in 1963, it forced a reduction of top-division teams from 74 (!) to 16, and raised the allowable (official) salary to DM 1200 / month, about $4800 at the time or $47k / month today, generous enough to make star players rich without under the table payments. Those were maximum salaries, though - most players would be making far less. And the players’ union was only formed in 1987, mostly to protect the rights of lower-division players; it’s unclear if there was a meaningful salary floor even in the top division prior to that.

Today’s landscape of women’s football is constrained more by economics, than by any romantic notions of amateurism held by the aristocratic people in charge of European soccer governance in the early 20th century (as the men’s leagues were). So as the economics of the women’s game advances,17 there won’t be the same struggle for a legal framework to pay players what they’re worth. But it also took decades for the men’s game to get there, even in England. We shouldn’t judge women’s compensation against the men’s leagues today, but rather against the men’s leagues at an equivalent point in their development. If we start from the first professionals-allowed women’s league (Sweden’s Damallsvenskan, in 1988), it was 13 years until the first fully-professional league (WUSA in 2001), and 25 years until the first financially-stable fully-pro league (NWSL in 2013), compared with it taking 35 years in the men’s game. They’re ahead of schedule! Which might be small comfort to fans and players today, but it does suggest that “we’re doing our best!” isn’t just cover for apathy.

Pay and Payrolls

All this talk about contract status and league stats is nice, but ultimately what we really want is to see women’s footballers get paid, and paid well, for putting on a show worthy of any other pro sport. Right? This is the natural order that sports fans expect: Top stars should make a fortune, average players in top leagues should make a very good living, and at the secondary leagues and developmental levels of the sport, players should still make enough to have dignity and be able to devote themselves to it as a career. But that’s a lot of “should”s, and to merely assert it - e.g. “the women are underpaid! Look what the men are making!” - gets the cause and effect backwards.

Making a Living Killing

In most jobs, there’s some function you perform, men and women can almost always do an equally good job, and therefore everyone doing it should be paid the same. You’re on a widget assembly line? Everyone around you, who’s similarly situated, should be similarly paid, regardless of gender. But that logic breaks down when we’re talking about performers, people in the entertainment business, because they’re not merely employees, they are also “the product”. Pro athletes are not interchangeable. If you’re a product, then what you earn is proportional to what people are willing to pay to see you (live, or on TV), or to have you sponsor something. Much like bonus-heavy pay for salespeople, the term is “you eat what you kill”, i.e. you’re paid based on how much money you, personally, bring in the door for your employer. It applies around the entertainment world, from movies to music to TV and even beyond. Or in the words of an industry insider:

“The central axiom in sport is that talent follows money, eyeballs follow talent

and money follows eyeballs. “

- Phil Carling, Head of Football, Octagon Worldwide, quoted by FIFPro

The logic of that phrase suggests that as the financial situation of the women’s football industry keeps advancing, so too will the pay, both at the top, median and bottom rungs of the prestige ladder. It’s not magic, it’s just economics. We can track that progress through many measures. And sooner or later, that feedback loop will close the gap by enough that the “shoulds” will grow less strident,18 and everyone will agree that sufficiently talented women’s soccer players can make great money, and the real challenge will be just getting in the door to do so.

But let’s put “should” aside for the moment, and just focus on “is”. What do we know about the state of pay in the women’s game today?

Payrolls and Financial Context

Deloitte’s June 2023 annual review of football finance did a deep dive on WSL clubs, and particularly their payrolls. It noted a growth from 2020-21 of average club wages being £1.5M ($1.9M), a crazy 92% of revenues, to 2021-22 with average club wages at £2.1M ($2.7M), down to a slightly-healthier 78% of revenues.

So the first thing we might ask ourselves is, “are those numbers good or bad? how can I even judge?”. The second thing we need to ask will be whether they reflect a short-term investment for a long-term payoff, or look more like a spending arms race that will leave its losers financially ruined.

Benchmarking vs Men’s Pro Sports

To take that first question, before we judge a payroll ratio as “healthy”, we should at least look at some other benchmarks. Firstly, note that these WoSo wage costs include not just players but also coaching, training and business staff - so, the entire club’s payroll - and thus are harder to compare to leagues that publish payroll data but only for the team’s playing roster. But we can take a crack at putting this in context.

In the American “Big 4”, the revenue share going to players is roughly 50-50:

The NBA has collectively-bargained to give players 51% of basketball-related income; it had been 57% in their 2005 CBA, but then 22 of 30 teams lost money and the league engaged in a lockout in 2011 before the sides agreed on the lower number, which as far as I can tell persists today.

In the NFL, it’s roughly 47-48%, with the denominator likewise not including some things we’d call team revenue such as stadium naming deals, gambling revenue or corporate hospitality at games. The NFLPA says 48% is a minimum.

The NHL sets it at 50%, with some escrowing but fewer sketchy carve-outs.

MLB does not have a set ratio in their CBA, and the results put it around 45% of revenue, but historically if you include benefits it has been closer to 50%, and if you further include the minor leagues (which the MLB clubs subsidize, so it’s a real cost to them) it’s closer to 56-57%.

How can we gross these numbers up to be comparable to the all-in wage cost ratios published in soccer? We have a few clues. This 2018 article on the NBA got some inside data, and gives percentage ranges for team staff costs (coaching, training, medical) at 10% for small-market teams and 6% for large-market teams; some teams also include their 2nd-team (G League) expenses of $3-5M in the number. It also lumps executive salaries / business staff, which is still payroll, into “business operating expenses”, alongside rent, insurance, and debt service, all of which would not be part of any team payroll ratio; but for the sake of comparison, those numbers run at 16-18% of the total. Let’s guess that business/executive compensation runs at 4-5% of team totals and thus ballpark 10-15% of total expenses as what to add onto player compensation; this would mean the NBA is at 60-65% of total wage cost as a % of revenue.

In the NFL, the league’s only publicly-owned team is the Green Bay Packers. Their 2022-23 and financial reports put their “team” expenses (distinct from “players”) at 9.5-10.1% of revenues; “sales, marketing & fan engagement” comes in at 12%, and “general and administrative” around 12-13%, a minority of which would probably be staff costs. If we make some assumptions19 we could figure that 15-20% of revenues go to non-player salaries and benefits, so 63-68% of the total.

The same guy who did Sportico’s MLS and NWSL valuations, Kurt Badenhausen, has looked at MLB in the past, too. He points out that the Atlanta Braves make their numbers public (historically a part of Liberty Media); For the first 9 months of both 2022 and 2023, their baseball operating expenses were ~81% of baseball revenue, while “selling, general & administrative” (SG&A) was an additional 15-16% in both years; the team reports a 5-10% accounting loss after depreciation. A little math on their statements suggests the Braves spend ~70% of revenue on salaries.

In men’s soccer, the payroll ratios are somewhat notorious for being uncapped and unregulated by anything other than ownership’s capacity for enduring financial pain; a perusal of Swiss Ramble’s decade-long chronicling of this (old site here) can suffice for proof. As a result, the vast majority of clubs are routinely unprofitable, and are run more as vanity projects (With the hope of recovering one’s investment by selling at a bigger number to the next vanity owner) than as businesses committed to making a return. Deloitte illustrates this in their latest (June 2023) review of football finance:

That’s an average loss of € 30M / year / club for French first-division clubs, each of the last 3 years. Italy a bit over €20M / yr loss per club. The cause? Trying to keep up with the Premier League’s Joneses on payrolls is culprit #1:

That suggests that for healthy leagues in a healthier year (2020-21 had pandemic-related exceptional constraints), somewhere in a 60-70% band makes sense and should yield profitable clubs (England, Germany, with Spain slightly above), while getting up to 80%+ makes your league a financial basket case. That doesn’t mean we can lay this situation at players’ feet, since the clubs have to decide what contracts to offer, and nobody is forcing them to do anything. It just means clubs are giving into temptation rather than pragmatism and long-term planning - with a healthy portion of league managerial incompetence to compound things. But the clubs in that 60-70% band are doing fine, on average. Some of Europe’s 30 biggest clubs (per Deloitte’s latest men’s Money League data) are well below that: Eintracht Frankfurt bottoms at 41%, Napoli at 42% (thus posting a record profit), AC Milan 45%, Tottenham at 46%, Arsenal and Manchester United at 51%, Real Madrid 54%, Bayern Munich and Borussia Dortmund at 56%, even Manchester City is at 59%. They are the big winners, while everyone else is frantically trying to spend money they don’t have trying to keep pace or catch up.

MLS is a massive exception to this “winner-take-most” financial situation. To ensure that every team in the league can usually make money, the league imposes a fairly strict salary cap20, and as a result having player expenses far below other larger leagues - this 2019 article claims it was then around 28%, having been <20% prior to 2012. Those numbers do not include benefits and other forms of player compensation, and the compared-to leagues don’t clarify whether these are player-roster-only figures, but regardless, MLS is the example of the bottom end of what soccer teams can get away with spending on talent.

The Big 2: Pay in the WSL and NWSL

So to return to the WSL club-by-club chart above, we can now draw the conclusion: paying out 92% of revenues in 2020-21 was insane, and even going down to 78% in 2021-22 was nearly as insane, and very unsustainable. The business justification, I’m sure the clubs would say if asked, is that they are investing in growth. That’s a reasonable thing to say in principle, because even the non-club investors in, for example, the NWSL, are doing the same thing: They’re building stadiums, hiring large staff to drive large pools of season-ticket holders and sponsor deals, some of them surely losing money at first as things get going. The idea is, we (the owners) have to spend money to get our fanbases to the point where the clubs are financially stable and profitable. The rapidly advancing attendance numbers in NWSL (and rising club valuations) prove that there is a credible investment thesis, one that can pay off.

But that logic doesn’t extend to the player payrolls, necessarily: you want to be able to afford a roster of full-time pros, and you might need to pay whatever is necessary to get a few marketable stars,21 but you don’t have to spend more than that on talent, because the justification ends there. Spending more than that on payroll is done solely to put out a better team and win more games. That might please the fans, and thus have some degree of ROI to it, but it hits diminishing returns (see the above ruinous arms race in men’s football), and so we’d have to call it '“vanity” if done to a degree above that ~70% benchmark. Which WSL is still at, despite a supposed salary cap.

The WSL also exhibits the top-heavy financial pattern visible in most top football leagues around the world. Since the clubs’ financial statements usually include not just staff wages/benefits but also an employee count, we can look at average pay per-employee, to get a feel for the compensation levels:

We can see that Chelsea (which spent almost $6M on wages and benefits, $150k per-employee), along with Arsenal and Man City, are a big leap above the rest. And that they’re paying ~3x better than the bottom half of the league, who hover around $2M in personnel expenses and average $38k per employee. And that (from the height of the blue line above the comparable green bars) they also employ more people on the footballing side, reflecting greater resources in coaching, strength and conditioning, nutritionists, mental health, and so on - reinforcing and persisting the edge they have on the field.

NWSL doesn’t publish club-by-club revenues or payrolls,22 so if we want to estimate their health, we have to make certain assumptions. The earlier-mentioned Kurt Badenhausen put out his 2023 NWSL club valuations last October, and with it an estimate of club revenues. These totaled ~$112M for the league’s 12 teams, or $9.4M per club. The salary cap for the 2023 season, meanwhile, was at $1.375M, with an additional $600k in “allocation money” available23, for a total max payroll of $1.975M. A reasonable assumption would be that clubs used half of that allocation-money max on average, implying that player pay averaged $1.675M per club - which would only be 18% of club revenue. Minuscule, given the accelerating financial status of the clubs. We can’t make the same assumptions as with men’s pro sports that the rest of non-player staffing costs amount only to 10-15%, because we know they’re spending to grow. We know (above) that NWSL clubs in 2019 averaged 25.4 admin staff and 8.4 technical/coaching staff, which more than exceeds the size of their first-team roster. But even if those staff average $50k each in salary + $10k benefits, that’s just another $2M in staff expense, or a total of 40% for staff costs. You might assume staff and salary growth in the 4 years since 2019 and arrive at a rough figure of 50% for staffing costs. And we can note the 2024 cap reflected that revenue growth, as it nearly doubled to $2.75M. But that would likely just keep the total staff costs around that 50% figure. And so unless I’m way off, that’s much, much lower than comparable leagues anywhere, and suggests NWSL is being run under very tight cost controls.

Monopolist Behavior?

The idea that the richest women’s football league in the world would also be the stingiest with pay, as a percentage of revenue, is perhaps surprising. A reasonable person might suggest that this derives from abusive monopoly power. Monopolies, as capitalists can tell you, are arguably the primary path to profits, and regulators correspondingly worry about their power to extract excess value from consumers. But the NWSL is not obviously a monopoly (it competes globally for talent, domestically against men’s football and other sports, and even within US women’s football, is facing emerging competition; it doesn’t really have much pricing power).

A different idea from economics might help resolve the gap: market share in an industry usually follows a power law distribution, which is one where the leader (#1) is not merely a little better off than #2, but has a substantial % edge over #2, which in turn has a substantial % edge over #3, and so on down. You can see this in, for example, market share of songs on the Billboard Top 100:

Or perhaps for a more-durable advantage, we might look at market share among sporting goods, or foods:

Basically in most industries, being #1 is a much greater financial advantage and return, relative to #2, than being #2 is relative to #3 (and so on). Down below the leaders, everyone is competing furiously, has no particular differentiation in brand, and thus likely doesn’t make much profit. So even if you’re not a monopoly, if you can muscle your way into a leadership position in an industry, you can still extract value.

What I think we’re seeing is that the NWSL is motivated to increase player pay, but only to the extent that it keeps them ahead of WSL as the #2 women’s football league, and ahead of the WNBA as the #2 women’s sports league in the US. They don’t have to outbid the WSL for every player, nor do their clubs have to be way more attractive as a women’s sports sponsorship opportunity than the WNBA teams - they only have to be a little more attractive, or pay a little better. Their economics are dictated by what their closest competitors can do, and any difference between that and what they could do if pressed, can be kept as profits. And until and unless they get pressed on pay, they can take those profits and build stadiums, market to build fans and fill those stadiums, and other growth-oriented activities.

Players will get a bigger slice of the pie almost by-default, to the extent it keeps the league as a world leader and allows the NWSL to sell a story about women’s empowerment and such. But beyond that share, the league doesn’t have much financial incentive to spend more on player payrolls, even though they could. So I expect the next NWSL CBA, in 2027, to be an absolute financial doozy.

The Big Fish

We can see this thesis proven out by the top contracts handed out in the last 5 years or so. Before 2019, the league was struggling to reach any sort of stability, and probably didn’t think much at all about “staying ahead” of WSL or any other league.24 In 2019, two-time NWSL MVP Sam Kerr butted up against the league’s then-maximum salary of $50k, and decided to sign with WSL club Chelsea for a reported $500k / yr, i.e. ten times as much. Combined with the high spend of other world-leading clubs like Barcelona and Lyon paying $600-700k to the very best players in the world, the narrative changed about where the world’s top talent wanted to play. Planet Football asserted that the WSL “pay[s] its players significantly more than the NWSL”. Australia’s annual player survey found that “the league players most wished they could play in” had switched from the NWSL getting a majority, to now 62% saying WSL and only 11% naming NWSL. The WSL has 31 broadcast deals of which 29 are international. I myself noted a growing amount of crowing by European soccer fans and publications, claiming that Europe was restoring itself to its rightful place atop women’s football. That the NWSL couldn’t afford the best players anymore, or even that its tactics are outdated.

Well, if Europe’s emergence in 2019-2022 was A New Hope, we’ve now arrived at The Empire Strikes Back.25 With its brand as a global leader at stake, and with its emerging financial edge even over huge European clubs willing to deficit-spend, we can see the NWSL’s response in the form of the new top-end contracts for star talent:

Dec 2021: Alex Morgan traded to SD, where she signed for $250k x 2 yrs

(Marca claims it was for $450k/yr but that seems unlikely)Jan 2022: Christine Sinclair re-ups with Portland for $380k x 1 year

(allegedly; source is sketchy and there are reasons to doubt the number)Feb 2022: Trinity Rodman re-ups with Washington for $281k x 4 years

Jan 2023: Marta signs with Orlando for $400k x 2 yrs (up from $41k in 2017)

Jan 2023: Megan Rapinoe re-ups with Seattle for $250k x 1 yr (some say $447k others $473k, and some say she made $400k / yr in her 2020-2022 deal)

Mar 2022: Sophia Smith re-ups with Portland for $300k x 3 years

Jun 2023: Naomi Girma re-ups w/ SD for $200k x 3 yrs (then-league max)

Dec 2023: Maria Sanchez re-ups with Houston for $375k x (3 or 4) years

Dec 2023: Crystal Dunn signs with Gotham for >$400k x 3 years

Jan 2024: Mallory Pugh, re-ups with Chicago for $500k x 5 years

Jan 2024: Portland sends a $318k transfer fee to Chelsea for Jessie Fleming, and they are probably not paying her less than that annually

Jan 2024: New club Bay FC pays a transfer fee to Manchester City for winger Deyna Castellanos and signs her to $450k x (3 or 4) years

Feb 2024: New club Bay FC pays Barcelona $162k for their striker Asisat Oshoala, and pays her an as-yet unreported but probably fat salary, on a 3+1 year deal

Feb 2024: New club Bay FC pays Madrid CFF a world-record $788k for winger Racheal Kundananji, nearly doubling the previous world record, and signing her to $500k x (4 or 5) years. If Bay were a patron at a bar, the bartender would have cut them off by now.

While this surge in long deals with big announced salaries may be as much a PR move as a financial one, it is a clear upward trend, with clubs flush from the massive 2023 attendance and new TV deal. It is also still clearly far less than they could choose to pay for the world’s top talent, collectively, if they wanted to. Over at Barcelona, 2x Ballon D’Or winner Alexia Putellas is in a dispute where the club is offering her €800k and she wants €1.5M per year (up from her current €600k). Although I have no inside info, her leverage may well be to solicit offers from NWSL clubs, for whom signing her would be the coup of all women’s football coups, and who credibly have the money to scare Barça’s boardroom.

Now, that’s just for the league’s top, most-marketable stars. And it’s not a totally one-way trend of NWSL keeping its top talent and adding more global stars: e.g., last month Arsenal signed USWNT right-back Emily Fox out of the NC Courage, and USWNT midfield mainstay Lindsey Horan has been at Lyon for several years after a big transfer. But looking at the numbers overall, the NWSL is clearly now making an effort to keep its top stars, and spending for global top talent when it’s willing to come.

How the Other Half Lives

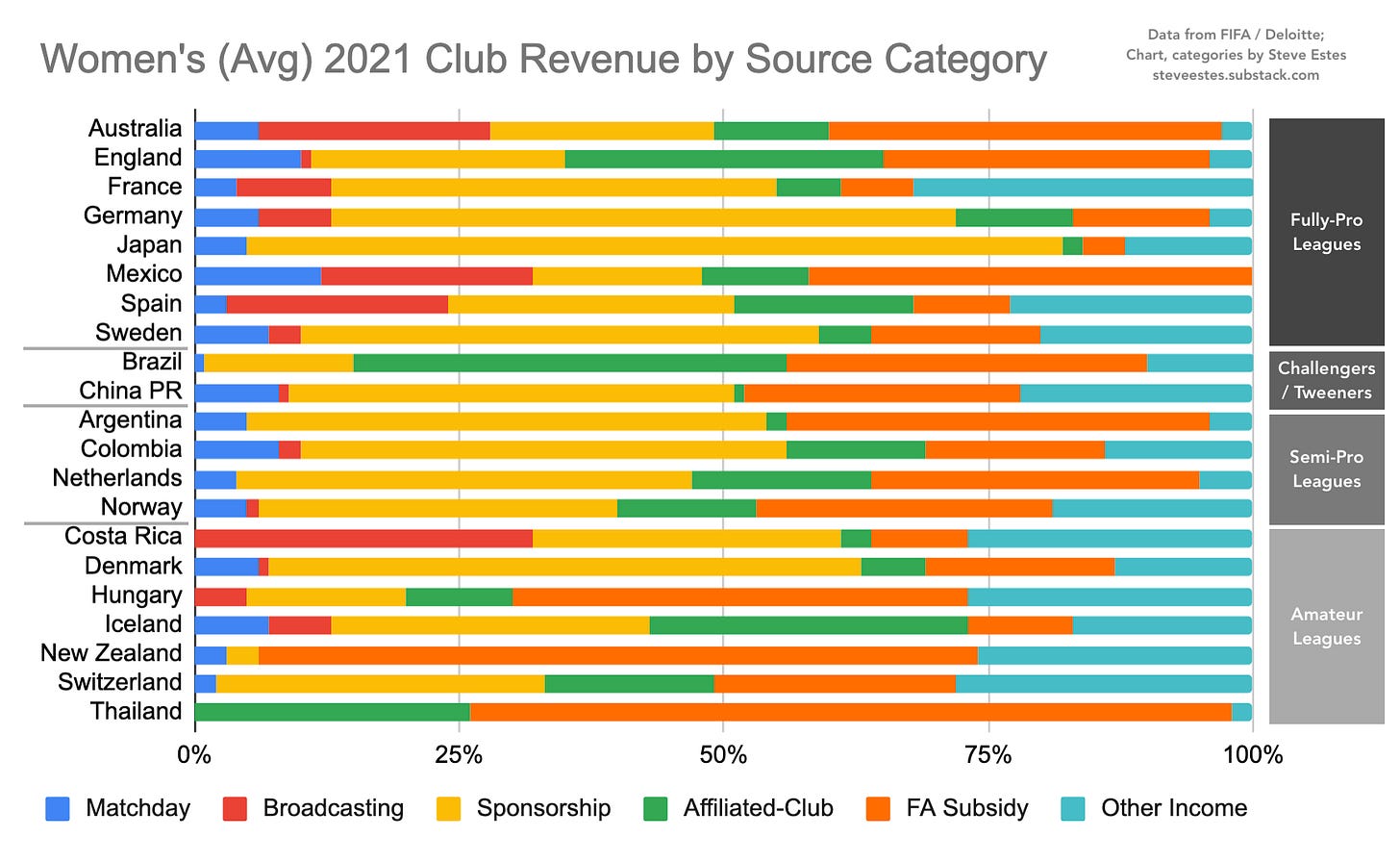

An excessive fraction of media attention in women’s football today focuses on the NWSL and WSL (and Barcelona / Lyon), to the exclusion of other leagues. But if that’s the top of the pyramid, we do know something about the other tiers, too. The Deloitte benchmarking report, in 2021 (and sadly not since) asked leagues for category breakdowns of their average club’s revenues and expenses. We covered revenues in the last post, but I’ll re-post the revenue-category breakdowns here:

For the expense side, we have a slightly-different set of 23 leagues giving data26, and they break it down as player payroll, vs support staff and other categories:

So we can see that even just purely on player wages, there is considerable variation between the leagues.

The overall average across ~285 reporting clubs had player payroll at 38% of costs.

Average total payroll (players + coaches + admin) is 68% of costs, though because most clubs lose money, it is probably a higher percentage than that as a fraction of revenues. Longer-term, I expect most leagues to stabilize in that 60-70% band representing financial stability in mature sports leagues.

Australia is the only pro or nearly-pro league that spends 60% of revenues on player wages; average for the pro leagues is more like 45%.

Japan spent even less on players than than what (we assess) the NWSL does, a mere 10% of club expenses; however, this data was from before they became a fully professional league in the 2021-22 season.

Taking total payroll (player + staff costs), a few leagues get above 80%, our “very unhealthy” threshold: Australia, China, Colombia, and in the amateur ranks, Iceland and Thailand. Nigeria and Sweden are in a danger zone.

Non-Playing staff (coaching + medical + admin/business) seem to average 20-25% of spend among pro and nearly-pro leagues, roughly in line with what we estimated for the mature men’s pro leagues as a benchmark. The numbers range more widely for the amateur leagues, where revenues and spend are going to be volatile because they are not fully operating as businesses in the first place.

The semi-pro and amateur ranks seem to often spend more on coaching than they do on player compensation. That surprised me. But maybe those who would coach a team like that could get another job as an assistant at a more-professional men’s or youth club, if they weren’t offered a proper salary, whereas the players have few alternatives within the industry (and mostly have second jobs anyway). In other words, the players are “the product”, but the coaches are employees like in any other industry, more interchangeable, and so the pay is more standardized.

You would think matchday ops costs would be proportional to attendance / matchday revenue, but you would apparently be wrong. There is clearly some correlation - see high spend in Mexico, Nigeria and Germany, middling spend in Brazil and Australia, and surprisingly low spend in France, Sweden and Norway. Surprises to me include China spending pretty robustly (reinforces their claims of attendance and revenue), same with amateur leagues in Costa Rica and Hungary, while South Korea is spending 21% of the budget on matchday despite reporting only 300 fans per game.

In my view, nobody is doing enough marketing, but at least we can say that Germany, China and Netherlands are trying. Some clearly are not, including Australia, France, Mexico and Brazil. Some marketing spend will be sponsorship activations, depending on how they counted it for reporting - in which case, it’s a “spend money to make money” situation.

Where we have these breakdowns as well as club revenue numbers, we can make some assumptions27 and back into an estimated payroll and avg-per-player salary numbers:

Again, we can throw out the Japan number, as it’s surely very different today. China (highlighted) is hard to believe,28 and frankly both the revenue and the wage % are suspect in my eyes (But if they’re true, that’s awesome!) And we lack sufficient data for the biggest leagues, including USA, ENG, GER, SWE and Spain. But this still tells a story: even in nominally fully-pro leagues, the average player compensation is still only like 30-40% of the country’s median wage. In Australia (and Norway, and Korea) it’s even worse than that. This has likely improved somewhat since the data year (2021). And we should note that if a league has well below 100% FPIS (Football as Primary Income Source) for its players, then it may well be that some fraction of players get essentially nothing, but for those FPIS players, the pay is meaningfully better than this suggests.

But even as an estimate of what the league average player gets, what her experience is,29 it still suggests that football is not a viable career unless (A) you’re a star within your league, or (B) you can somehow play in the world’s top leagues (still a rare thing for non-stars coming from abroad). The median player in these leagues, even if lucky enough to be a salaried professional football player, is making poverty money and probably can’t sustain that for more than a few years in her early 20s. No surprise, then, that most players who aren’t in the NWSL / WSL tend to take second jobs to make ends meet. Chasing the dream is fine, especially in your 20s, but it doesn’t put food on the table. And this situation frankly isn’t that different than in the men’s game: there may be some immensely well-paid players at the top of the game, even in relatively poorer countries… but for every 1 of them, there might be 100 semi-pro or amateur guys with stars in their eyes thinking they’ll be the next Jamie Vardy. The main difference is the number of available well-paid jobs for men in the first place, ones where you can have a career for 10 years before moving on.

Stories of Progress

A headline of “most women’s football players aren’t well-paid today” is unsurprising - a dog-bites-man story. The encouraging and notable part is how that is changing, i.e. what we can see for a trend.

The deepest study of salary data for women’s pro sports is by Sporting Intelligence, which in 2017 did a special women’s-sports issue of their annual sports-salary survey. At the time, they estimated that 1,287 women worldwide were professional footballers (on a definition I would support30), compared to 137k men (106x the women’s count). And it obtained salary info for a dozen professional women’s sports leagues including 7 football leagues (7 of our Big 8, in fact, with Japan absent as they were then years away from going pro). In 2017, the pecking order of average salaries looked like this:

That’s right, in 2017, the NWSL ranked behind *checks notes* the Danish handball league. And was 4th among women’s football leagues, behind France (surely buoyed principally by Lyon), Germany and England, but already ahead of Sweden and Australia, which predated it by many years. With the exception of the NWSL, however, the leagues seemed to have only 50-60% of players on pro contracts (semi-pro, by our measure).31

With that as a baseline, let’s look at the NWSL over time. The league sets a salary cap each year: for 2023 that was about $1.4M (with a maximum salary of $200k), plus $600k additional “allocation money” teams can use on players above that amount, usually to pay marketable stars. While individual salaries have not been published, we can estimate some averages. And for all the glamour of their present media deals, the NWSL’s first years were absolutely ramen-noodles-for-dinner years for the average player. Courtesy of Equalizer Soccer, we can chart the league’s minimum, estimated-average and maximum salaries32, as percentages of the country’s median wage each year:

The story jumps off the chart, to me anyway:

When the league launched, they were paying everyone except the national-team players (whose pay was subsidized by US Soccer)33 essentially token amounts.

Minimums got better in 2017, but things really turned in 2020 when the league introduced Allocation Money, and that plus a big rise in salary cap took the league-average salary to $40k, about 60% of median wage.

Starting with the 2022 CBA, the league minimum reached around 50% of median wage (and will stay there, as the number is contractually fixed through 2026).

The league’s middle class has had quite a last couple years. Even with the expansion of rosters to a minimum of 22 players in 2023, the salary cap rises have driven the estimated average salary to approach the country’s median wage in 2022 ($67.5k), meet it in 2023 ($76k), and for 2024, if teams spend to the cap34, it will be $125,000 per year, which is 161% of US household median income. That’s the average! That’s what a graduate from a top MBA program initially makes!

The league’s maximum cap charge (which basically hand-waved away the higher salaries of USWNT players those first few years) has largely ceased to exist. It was supposedly $75k in 2022 and $200k in 2023, but I can find no mention of it for 2024, and I suspect there is no maximum anymore. After all, the league wants to now be able to offer whatever it will take to keep the world’s best talent in-house.

Those current league minimums of $36-40k from 2022-2026 aren’t amazing for the players who will earn them, but given the team-subsidized housing benefit and transportation perk, plus various other benefits, it’s absolutely livable in your 20s, or in a 2-income household. Meanwhile, the average number is staggering to me: it represents a 9x jump from 2017, representing a 34% annual growth rate. MLS, by comparison, has a minimum salary of $67k, and average player cap charge (so, not including designated players) is $438k. $125k average in NWSL is still several times lower, obviously, but it’s now in the same order of magnitude - and we’ll have our first NWSL players earning more than the MLS average this year, if we didn’t already.

Italy, meanwhile, is a good example of a still-developing league where we can look at the growth curve. Based on the federation’s reports, the trends of fan interest, sport participation, social media followings and TV ratings are all going in the right direction. Alongside it are payrolls. Prior to the law changing in 2020, the previous semi-pro in Italy era was embarrassingly paternalistic. As of 2017, league-champion Fiorentina had a total team budget of € 800k. In 2019-20, the payroll for the full 12-team league was € 4.4M, or € 367k average per team. In 2021-22, the last year of “dilettantismo”, it was € 6.3M (€ 525k average). In 2022-23, the first year of full professionalism, and subject to a league minimum salary of € 26k35, it rose to € 10.1M with now only 10 teams (€ 1.01M each), which for a pro roster of 22 players means an average of € 46k, higher than Spain and leaving plenty of room to both bring in top talent and also have budget left over for a payroll middle-class making above the league minimum. We don’t have per-club data, although chances are Roma and Juventus dominate the rest, in the manner of their neighbor leagues. But those salary minimums and averages seem “healthy” for a league in its first pro season: the 26k league minimum is 62% of Italy’s €41.9k median wage (above even the NWSL’s minimum, as a percentage anyway), and the league-average 46k is actually above Italy’s median wage! Even those on minimum deals are making money they can live on if they’re careful.

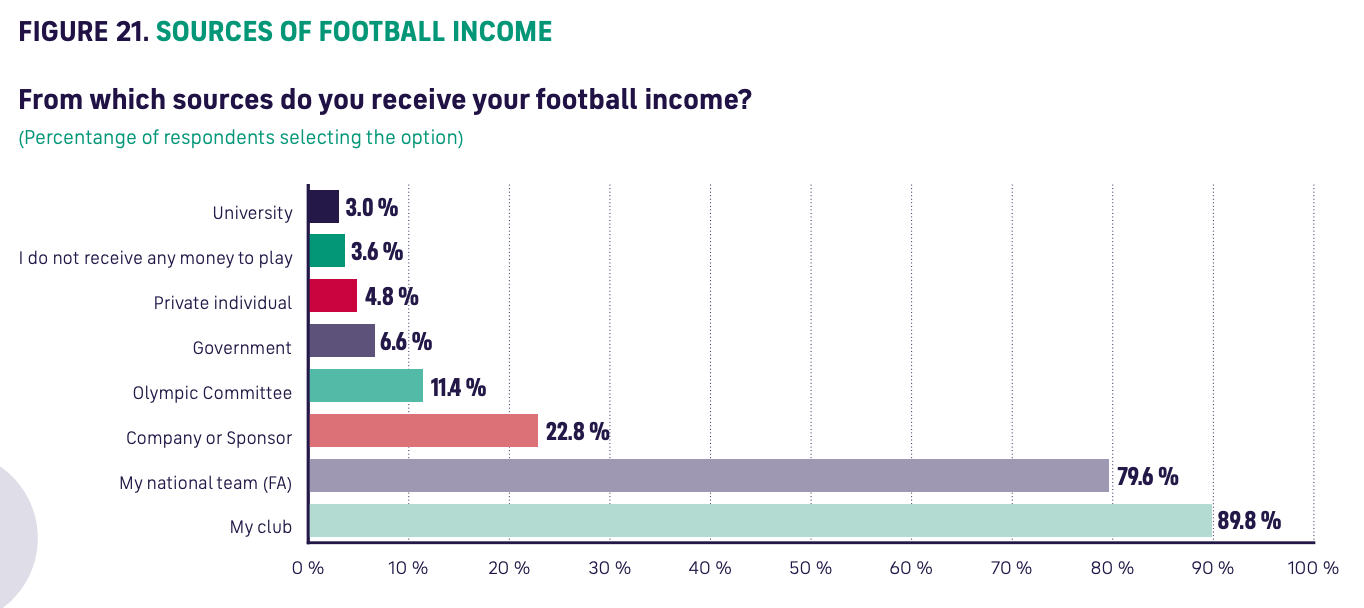

More globally, a Eurocentric (59% UEFA) panel of players reporting their salaries in late 2019 showed progress in monthly compensation between 2016 and 2018: a jump of between 50-80% at clubs, and a rise of 16-43% from national teams, depending on how you calculate it.

Elsewhere beyond Europe, data is more anecdotal, but speaks to the same rapid-development trend. In Mexico, prior to the 2018-19 season, there was a league-mandated salary ceiling of 2,000 pesos ($117) per month, a collusion for which they were later fined by labor regulators. For 2018-19 that was raised to 15,000 pesos ($750) per month, and since that season it has been uncapped. By 2021, players on $100-200 / month was reportedly present but uncommon, and the typical range of pay on a Liga MX Femenil roster was between $300 and $7,000 per month, with ~$1,500 / month ($17k / year) being the average for foreign-born players. That’s good progress.

Former player Naty Cardenas told her story this way:

“[Initially] I was paid around $180 a month; it was a real struggle, but my love for the sport made me stick through it, and sure enough, after signing to a different club, my income grew, and I was able to focus on playing,”

The league is very tight-lipped about salaries, but in testimony to Mexico’s Senate late last year, they shared that the average pay was 35,000 pesos per month, or about $24.5k USD / year - which would be roughly TEN TIMES the estimated number from the 2021 FIFA survey (above), and equal to 147% of the country’s $16.7k median wage - putting it within range of the NWSL’s ratio. While the 2021 number may have been an under-estimate, we also must conclude that the clubs have made a lot of progress on women’s-team revenue in the last few years, and much of that has flowed down into player payrolls. As a result, this has stemmed the tide of Mexican players going to the NWSL for a payday.

Sidenote: The Mexican Senate’s source documents also claimed this average salary was, at the time, 8th among global women’s leagues - but they don’t mention numbers, or who was ahead or behind. If anyone can find their data, please share!

We also have data from Australia. The A-League Women’s Players Association runs a survey after the season, and they got 174 players from their 12 clubs (at least 11 from each) to respond on a range of topics. The whole thing is fascinating, but for our present purposes, it gives the league’s salary-cap36 numbers:

This is in Australian dollars (1 USD = ~1.50 AUD), but translating to USD, it means that the league’s payroll floor/ceiling has gone as follows:

2021-22: $211k - $302k payroll range, min salary $10.9k, average per-player $12.1k for a 22-player squad (and each contract being 23 weeks long)

2022-23: $258k - $336k payroll range, min salary $13.8k, avg per-player $15.0k for a 29-week contract (24% growth year-over-year)

2023-24: $336k - $403k payroll range, min salary $16.8k, 35-week contracts (25% year-over-year growth)

Are those numbers impressive by NWSL / UWCL standards? No. But this post is about the women’s game growing to respectability, and for that, 25% growth in pay for 2 years running is nice to see. If you view them in the context of Australia’s per-club revenue and spend numbers, which 2 years ago looked kinda grim by the standards of fully-pro leagues (above), this suggests that they’re not in such a bad way anymore.

Non-Salary Benefits

FIFA’s report gives a view into the non-financial benefits that the athletes receive, too. While I don’t have much to compare this to on the men’s side, nor do we get league-by-league breakdowns, it’s worth noting that across 316 clubs in 34 leagues, those clubs offered perks at the following rates:

67%: health insurance

59%: food allowance (I assume this is usually a travel per-diem)

57%: housing benefits

36%: gym membership (presumably if they lack one at the club)

25%: education scholarships e.g. to university

23%: vehicle benefits

18%: relocation payments

9%: other

8%: N/A, we don’t provide our players with non-financial benefits

Some of these are surprising on the low side (33% make their players play without health insurance?!), but some might be truly substantial and easily ignored. Housing benefits, for example, I know from the NWSL included free group housing for players, which can amount to a lot of monthly expense (for normal people) that they didn’t have to spend. All told, depending on how these are structured, the value of these benefits may sometimes approach the total salary of some of the league’s less-well-paid players. It’s difficult to know whether the “player payroll” reported in the data above includes benefits and career support, or whether they’re an alternative expense category for the clubs - and if that’s done consistently. So this is another area where I hope we get additional detail in future editions, because it certainly matters as to the players’ overall well-being and financial stress.

Salary Caps

Left to their own devices, the pay for women’s footballers, like men’s footballers, is entirely up to the clubs and their own ambition and budgets. We’ve seen how those ratios look when they’re healthy (40-50% to players, 60-70% on payroll overall), and how clubs can bankrupt themselves by exceeding it. Unlike global men’s football, North American sports leagues have long adopted a precaution of instituting salary caps: maximum player payroll amounts that each team has to stay under. This has the dual benefit of restraining any team from spending themselves into oblivion, as well as leveling the competitive playing field. Big-market teams will thus make outsize profits, but their ability to simply buy titles and success is far more limited. The NFL and NHL have fairly strict salary caps, the NBA has a “soft” cap with Byzantine, kafka-esque rules to e.g. allow teams to retain their own stars, and Major League Baseball is nominally uncapped but institutes a tiered “luxury tax” for exceeding certain thresholds, whose proceeds are distributed to non-taxpaying teams. MLS, as covered, is nearly unique in men’s pro soccer in having a salary cap.

Salary caps are not, of course, to the benefit of players: any club who would have paid more for a player but-for league rules, is spending less than they would have, to the detriment of the player. Given the historical setbacks in establishing women’s soccer as a viable pro-sports business, it made sense for the players in the early years to give teams a lot of leeway in this regard. They are one view into a league’s financial health, and to the extent that they help all clubs reach a level of on-field success and financial viability, they’re probably (but debatably) a good thing. They are now more common in women’s football than they are in global men’s football: per the Deloitte report, 7 out of 34 surveyed leagues (21%) have a salary cap, up from 17% (5 of 30) in 2022, with Morocco and Sweden joining the list. I expect that frequency to expand (perhaps even among the men), because the upsides are obvious but the downsides can be mitigated by good collective bargaining.

Today, the NWSL’s salary minimums, and roster sizes, are set by collective-bargaining agreement with the players - but salary maximums, team salary caps, and other constraints, are determined solely by the league’s own judgment. We shared the NWSL’s cap numbers earlier for what they say about average player salary, but viewing them in isolation, they have gone from $200k in year 1 in 2013, up to $2.75M today. Here’s that annual growth rate:

We can’t necessarily assume that a cap of $X means teams are spending to $X, and there are cap-rules shenanigans here around national-team players not counting (until 2022); Australia has similar exclusions. But the picture this shows is a league that was growing OK for a few years, and then from 2019, has taken flight.

Australia’s cap was shown earlier: it went from $300k USD 3 seasons ago to $400k for this 2023-24 season, with exclusions for now-5 (originally 3) “marquee” high-paid stars per team. That figure was $100k USD (A$150k) in 2015, and $200k USD (A$300k) for the 2017-18 season (which also introduced the first minimum salary). They also have team salary floors roughly 20% below the cap; that’s a mechanism sometimes seen (e.g. in the NFL and NBA) to ensure players aren’t solely getting the downsides of a cap, i.e. that the intent really is competitive balance.

In Sweden, salary caps are new as of the 2023 season, at least per the Deloitte report - I can’t find any further evidence for or against it, partly because I don’t read Swedish. For the 2013 season, somebody on BigSoccer said their 12 clubs spent SEK 69.8M, which at the time was about $10.7M USD, equivalent to about $1.15M per club today - solidly in the middle of the world’s pro leagues, even without assuming further growth since then. Perhaps we’ll get more details soon.

England’s WSL, meanwhile, has something of a fake salary cap. Per the league rules, clubs must keep their player payroll (including bonuses, appearance fees, and various benefits) under 40% of their club’s annual revenue. However, as noted by the sports lawyers over at Sheridans, housing accommodations provided by the club are counted for a maximum of £5,000 (so spend beyond that doesn’t count), payments by the FA for national-team duty don’t count, any bonuses or prize-money distribution from Cup competition or UEFA Champions League participation doesn’t count either, and most of all, in-kind contributions from parent clubs (e.g. allocated revenue from shared sponsorship deals) are basically counted as revenue however a club likes. In practice, there is no meaningful cap, though complaints about its weak scope come from both big teams and smaller teams. This 40% rule has been in place since 2014, prior to which a hard cap existed (teams limited to 4 players paid over £20k); reintroducing one could be blocked by the players after they won greater representation through their union.

The salary cap is but one element of the competitive structure of the WSL under review right now. Last year, an independent government-commissioned report led by former player Karen Carney published its analysis of how to support and grow the women’s game in England. All commentators are taking its recommendations seriously because the UK government is likely to endorse and insist upon them to the FA. And while it covers many topics, from supporting grassroots youth development to enabling more international players on rosters to ticketing practices to parental-leave policies, a few recommendations are more relevant to us:

Establishing a minimum annual salary sufficient to avoid players going part-time

Accounting clarity, including specific disclosure of solidarity funding from a parent men’s team, and breakdown of revenue attribution from shared sponsors

A dedicated TV-broadcast time window free, from competing men’s broadcasts

They recommend against making the top 2 divisions a “closed league” (i.e. relegating teams out), believing it improves the drama and fan interest, and instead suggest that “appropriate financial regulations and licensing to prevent financial recklessness is preferable“

Reading the tea leaves, in trying to solve the problems of competitive balance, incentivizing investment and preventing financial calamity, the stakeholders in England seem likelier to find a salary cap palatable than they are to implement a closed league or other more-fundamental changes to league structure.

The Nigerian league, the NWFL, declared that it had a salary cap in both the 2022 and 2023 Deloitte reports. It’s difficult to find any detail on it, but in a country with GDP / Capita of just over $2k USD, the threshold for “living wage” for a professional is more readily achievable. As of 2018, some teams were owned by states (i.e. regions), and paid better, while some privately-owned clubs may pay only intermittently as funds can be raised. In 2022, the league had trouble conforming to a N150k ($100) monthly salary minimum as it was introduced, with some clubs having players at a quarter of that, or no pay at all. But if it takes, that minimum would amount to 55% of GDP/Capita, which is roughly where the NWSL got to with its 2022 CBA. I suspect that a salary cap would frankly be the least of the league’s concerns.

Finally, in South Korea, the WK League likewise claims to have a salary cap. According to an American playing there, Paige Nielsen, the teams are all backed by companies, and so the players are employees of that company - and paid accordingly. The teams may in fact be run without regard to profitability. However, there is a maximum wage, which was established with the league in 2009, and has remained the same since: 50 million won, equal to $37.4k USD / year. According to the head of the players’ union, many players reach that salary after about 5 years, and then can’t increase their earnings any further. So there might not be a salary cap per-team, but there is one per-player, and arguably that’s even more restrictive. But even if so, there are many footballers around the world, even in top leagues, who would be delighted to earn that paycheck.

Side Hustles

That Australian Players Association (PFA) report also gives a closer view into players’ choices to get a second job (or not). They report that in mid 2023, 60% of players had held a second job that season, down from ~70% the previous two seasons, and about equal to the last two pre-pandemic seasons. And in no great surprise, those who did have to work more outside of football were less happy about it:

Why do we care? This actually goes to the root of why the professionalizing of leagues is so important. In supplemental (anonymous) commentary in the Australian survey, the players candidly gave color to how this moonlighting affected their football, mental health and their ability to balance their time:

“Only able to work night shifts due to morning trainings, so it’s very hard to get adequate sleep after a night shift.”

“If my work and football commitments clash, I am expected by my coach to skip work (where I get paid more and am respected more), and I am expected by my boss to skip soccer, and neither care if you suffer financially or reputation wise for it.”

“It is difficult having to work an extra 40 hours a week just to get by, when many of my teammates don’t. This impacts my ability to perform, and takes away from what I am able to put into football, as well as takes away what I’m able to get out of it.”

“I just feel like there’s no time for anything else except football. Sometimes I feel tired and burnout enough playing the sport yet alone stressing out about outside commitments. Having to focus on life outside of football and money it has a real impact on mental health.”

The PFA made a great point about the risk and opportunity the issue presents:

The league’s economy is built on the quality of the football product and compelling stories.

If players and staff are not able to commit themselves fully to their craft, its progress is stymied. Full-time professionalism should be framed as an investment, not a cost.

In other data on that front, FIFPRO (the global players’ union) and the Chilean players’ union ran a ran a survey (summary here) of 1,100 first-division South American players in 7 countries (not including Brazil), last December. There were a number of interesting observations,37 but on the subject of job-holding, 43% held second jobs in total. Regarding pay, 27% were fully unpaid, 49% got paid but less than the legal minimum wage, and only 24% were paid more than minimum wage.

To FIFA’s credit, their (Deloitte’s) 2023 benchmarking report made “multiple job holding” a focus area, discussing the challenges that it presents. They surveyed 700 players who averaged age 26, across a fairly diverse set of 12 countries, and found:

27% held a second job, ranging from 5.3% in Brazil to 77.8% in Australia38

60% said they had a second job on a non-permanent contract, and 20% said they had a secondary full-time job (overlap with the previous bullet is unclear)

Of those with any type of secondary job, 49% earned under $5k USD from it

36% were also undertaking further education while playing

23% reported they took unpaid job leave to fulfill football commitments

72% perceived themselves as playing in a professional environment with a remunerated contract, however:

52% said that their football-related expenses were greater than their football income (putting them outside even FIFA’s definition of “professional”)

This represents progress from FIFPro’s first study in 2017 (full paper, or very good summary here), which was deeper (3,300 players in 33 countries). In that snapshot 6 years prior, only 18% had a written contract and got at least their expenses paid (“semi-pro”, or FIFA’s “professional”),39 compared with 69% in the 2023 Deloitte report.40 67% reported having a second job in 2017 (down to 60% in 2023). Those players reported an average of 27 hours / week worked in the 2017 report; for professional players alone, it was 20 hours / week. Likewise, 45% of players reported blending football with pursuing further education (down to 36% in 2023).

We also know something about “dual career support” that some clubs offer to their players. Most players are young and may have forestalled their education or developing other professional capabilities that they will later pursue, in order to focus on football. Recognizing the need for players to transition to other careers at some point, the Deloitte 2023 report gives stats on the forms of support offered by clubs:

It’s hard to gauge how much this makes up for otherwise-meager salaries in most of the world’s leagues. This might just be another dimension of “the rich getting richer”, with most of that support or benefits coming from the leagues that are already doing well and paying well. There’s some indication that it’s better than that - e.g. in the South American survey, 70% of players regarded the club’s provision of benefits and professional environment as “good”, 27% “normal”, and only 4% “bad”. But it does reinforce that we can’t just solely by salaries and payrolls. Which brings us to:

ABCs of CBAs

So the sport is bringing in steadily more money. If in entertainment, the rule is “you eat what you kill”, then the eating has been getting better. But if un-mediated, that rule also means the marketable talent bringing in that money - the stars - tend to eat the lion’s share of the gains as they percolate to teams’ payrolls. But this isn’t Broadway, or even the Women’s Tennis Association; it’s a team sport. And the less-celebrated players who provide the competitive context for the stars to shine want their cut, too. And as we know from every other pro sport, once the sport’s finances permit it, one of the first things the players want is a collective-bargaining agreement (CBA).41 In women’s football, what the players want out of a CBA above all is better pay and guarantees, putting a reasonable salary floor under the league’s non-star players. A close-second goal to that: to curb the most thoughtless humiliations and unprofessional elements of their environment, of which there can be many.42

Back in 2019 when there first started to be a pie worth dividing, NWSL player leadership was largely in the dark about the NWSL’s evolution of their league rules and pay structure, and lacked influence over it. But then in 2022, the NWSL and its Players Association agreed on a new CBA, by far the most generous of its kind (though not the first), and it in fact deserved all the hype that it got at the time. It can be read in full on the NWSL PA site, but in summary it provides:

Minimum salary of $35k in 2022, rising to $40k by 2026

Signed players per team: minimum 22, maximum 28, plus up to 4 on supplemental contracts

Minimum bonuses of ~$5k per player for individual or team achievements

50% of the revenue / prize money for any international club competition to players

10% revenue sharing of media deals from NWSL if the league is profitable, starting in 2024, to add proportionally to player pay

A road per-diem from $81/day in 2022 to $97/day by 202643

Team-provided housing (max 3 players / house) or a stipend equivalent

Relocation benefits for players moving teams

100% pay during pregnancy and maternity leave

Commercial air travel for road games more than 350 miles from home

Restricted free agency after 3 years of service and full free agency after 6 years44

Grievance dispute process, disability benefits, standards for hotels and working conditions, and various other typical union stuff